The Reactionary Tradition Out To Annihilate American Liberty

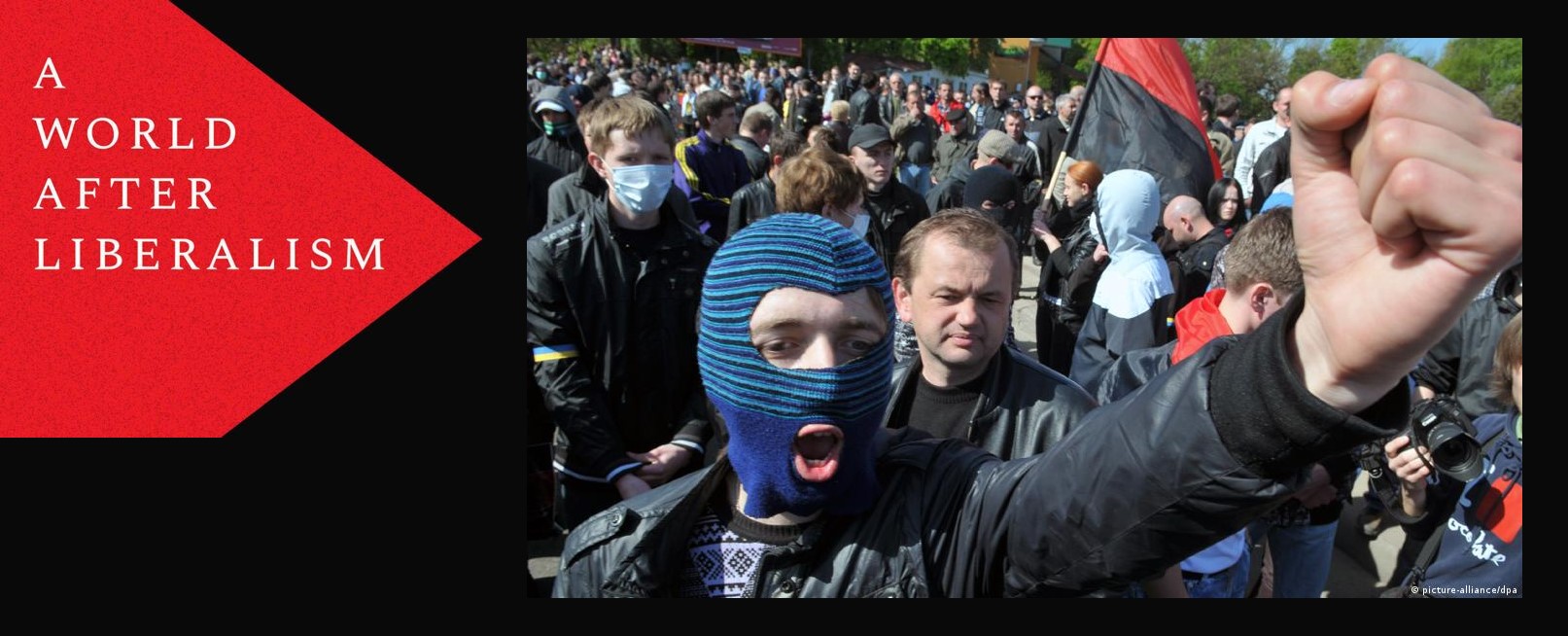

'A World After Liberalism' details the rise of a young right that finds reactionary ideas relevant and appealing.

A World After Liberalism: Philosophers of the Radical Right, by Matthew Rose, Yale University Press, 196 pages, $28

For portions of the MAGA right, the stakes in politics seem unbearably high. They imagine their elections stolen without consequences, their children menaced by transsexuals in the schools, their fathers' manufacturing jobs shipped away by globalist corporations that mock their values. People whose worldviews sicken them seem to control every citadel of political and cultural power and to brook no opposition.

Even President Donald Trump seemed powerless to shift America back to the country they wanted. And so several institutions and thinkers of the intellectual right have declared that it's time to take the gloves off in a way even Trump would not. It's time, they argue, to fight against "liberalism"—not just the attitudes associated with the Democratic Party, but the historical idea of a social order based on people's ability to make their own choices about what to do with their lives and property, to live and travel where they wish, to choose meanings, family structures, attitudes, and lifeways freed of any obligation to national or ethnic traditions. They want the American right to get tough and to crush progressivism at its root.

Thus, there has been a small intellectual revival of mostly forgotten or despised thinkers often dubbed "reactionary." In A World After Liberalism, Matthew Rose of the Morningside Institute assesses five of them: Oswald Spengler, Julius Evola, Francis Parker Yockey, Alain de Benoist, and Samuel Francis.

Just six years ago, a book covering these characters would have seemed a mere curiosity for those who get a frisson of forbidden delight dancing on the intellectual edge, exploring paths so far from an acceptable national norm that they have the louche appeal of the intellectual freak show, not relevant to actual American electoral politics.

But as Rose notes, a younger right is rising that finds reactionary ideas relevant and appealing: "Republican politicians won't know them all…but their young aides will," he writes. "At conservative magazines, senior editors don't read them, but their junior staff do." The ranks of the self-styled "new nationalist conservatives" are filled with these reaction-curious types. They "take as a premise," Rose explains, "that American conservatism as it had defined itself for generations is intellectually dead. Its defense of individual liberty, limited government, and free trade is today a symptom of political decadence."

Many libertarians have believed they had allies on the right, in fighting for those principles against the progressive left. To the extent that Rose's reactionaries and their epigones guide the right side of the spectrum, the libertarian is more than ever trapped on a hellish battlefield watching two dominant forces fight to destroy American liberty, for different goals and from different premises.

These reactionary writers see, in Rose's words, "humans as naturally tribal, not autonomous; individuals as inherently unequal, not equal; politics as grounded in authority, not consent; societies as properly closed, not open."

ose regards Spengler, an early 20th century German historian who predicted the death of the West, as the "intellectual godfather" of the reactionary right. Spengler believed that Western civilization had a Faustian drive toward the achievement of greatness. And to Spengler, liberalism—with its supposedly squalid obsessions with political equality and with meeting each other's needs through peaceful trade—"detests every kind of greatness, everything that towers, rules."

Rose interprets Spengler as believing "there is no place outside of a particular culture from which human beings can think, feel, or communicate"—an idea generally used to endorse authoritarian attempts to defend cultures from allegedly corrupting external influences. In its obsession with the vital importance of group distinctions and differences, reactionary thought starts to resemble woke arguments for irreducible cultural relativism.

Next: Julius Evola, a 20th century Italian occultist with a substantial far-right following. The pop reactionaries seem to believe that any "normal" person should obviously be disgusted by the excesses or laxness of modern mores. But those without some prerational neurotic aversion to having choices about love, family, religion, how to work, and where to live would more likely dismiss Evola as an absurd freak coping with his own problems and anxieties by insisting human beings are essentially like dogs requiring a system of strictly imposed outside discipline.

Such reactionaries believe, without historical evidence or even a compelling theory, that people are happier and flourish better with fewer choices, with a life less rich with the comforts and options provided by markets and liberalism. It is usually hard to believe even they would be happy in that sort of life, given that they tend to be intellectual misfits and malcontents. Liberal modernity, in Evola's time and now, has certainly seen lonely people dissatisfied with the choices they've taken, but that gets nowhere close to proving that a nonliberal society would more assuredly generate a greater proportion of truly satisfied, flourishing people.

Francis Parker Yockey was an anti-Semitic international man of mystery in various post–World War II underground movements, both fascist and communist, that opposed America's festering liberalism. He argued that the West in its best sense lost World War II, which he saw as a German effort to, in Rose's words, "build a society that could escape the slavery of communism and the anomie of liberalism."

Less important perhaps than his continued ideological influence—he's the figure in this book you are least likely to hear about from anyone trying to be part of an aboveground political conversation—is the bizarre and colorful figure Yockey cut. He was eventually arrested in 1960 with luggage filled with seven birth certificates, passports from Germany, Britain, Canada, and the U.S., an address book entirely in code, and "drafts of three pornographic short stories." The best thing Rose can say for him is that his willingness to shape and eventually ruin his own life in pursuit of his vision of Western greatness shows a man who was "deadly sincere, his words having been sealed by the testimony of his life."

By contrast, Alain de Benoist, one of the fathers of the French New Right, shows where reactionary thinking has the most policy implications. American politicians will not be able to restore preliberal lifeways and destroy the global market economy, but they can pursue immigration policies that keep people of different ethnicities and cultures out, or try to.

De Benoist's "identitarianism" insists that preventing the free movement of goods and human beings is in service of humanity's glorious heritage of difference. No true democracy can exist, he says, if the "people" are not truly one distinct people; de Benoist insists, as Rose sums it up, that "human identity is always mediated through group membership" and that "human beings do not exist, even in their most private aspects, as mere individuals." No one, in other words, can be happy not living roughly the same way as some long-dead ancestor they never met.

The fifth figure in Rose's quintet is Samuel Francis, best known to the mainstream as a columnist for The Washington Times. Francis wrote presciently in the 1990s about the coming Trumpist movement of "middle American radicals" against global trade and liberal values. In his later years he felt it vital to add that the only valuable middle American was a white middle American.

Reactionary ideas are woven through MAGA and its intellectual enablers. In right-wing publications such as American Greatness and The American Mind, we see arguments that order outweighs liberty, that autarchy and cultural purity outweigh free markets and free movement. Those attracted to these ideas suggest that the "other side" is not "playing by the rules," and therefore that state action to crush those who believe things the right does not is warranted (with a wounded insistence that They started it!). These neo-reactionaries value, or say they value, the Spartan virtues of toughness and violence over tolerance, trade, and other allegedly weak cosmopolitan ideas that in fact make life rich and salubrious.

Libertarians—alone again, naturally—shouldn't accept that because reactionaries hate the left so very, very much, they must be embraced as allies. A proper libertarianism seeks the personal liberty that each of those sides wants to squelch. Both reactionaries and progressives are menaces to the civic peace that a flourishing civilization relies on, since both seek to remake the social world to their liking by force.